"The action of the court in this case has somewhat embarrassed the Department."Secretary of the Navy Gideon WellesMarch 18, 1865Aboard the sidewheel steamer USS Baltimore, anchored on the James River a century-and-a-half ago, a 33-year naval career hung in the balance. Commander William A. Parker, who had until recently commanded the Fifth Division of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron, stood accused of, among other things, "withdrawing from and keeping out of danger to which he should have exposed himself," and "[f]ailing to do his utmost to overtake and capture or destroy a vessel it was his duty to encounter."

![]() |

This print by William R. McGrath in the Hampton Roads Naval Museum collection shows the powerful ironclad Onondaga patrolling the James River in more tranquil times. Although successful in damaging the ironclads of the Confederate James River Squadron without suffering a single fatality or serious damage during the Battle of Trent's Reach in January 1865, the controversial decision of her commander, Commander William A. Parker, to withdraw during the first hours of the battle led to Parker's court martial in March. |

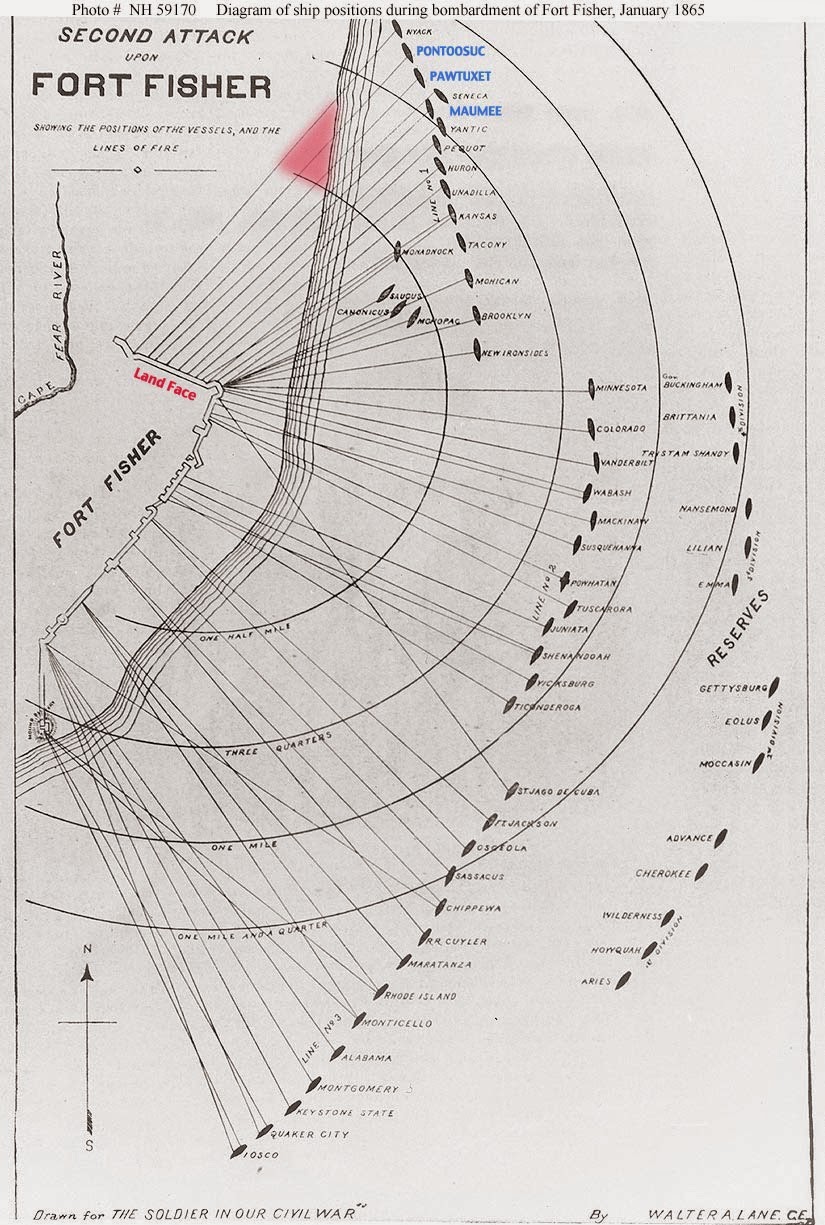

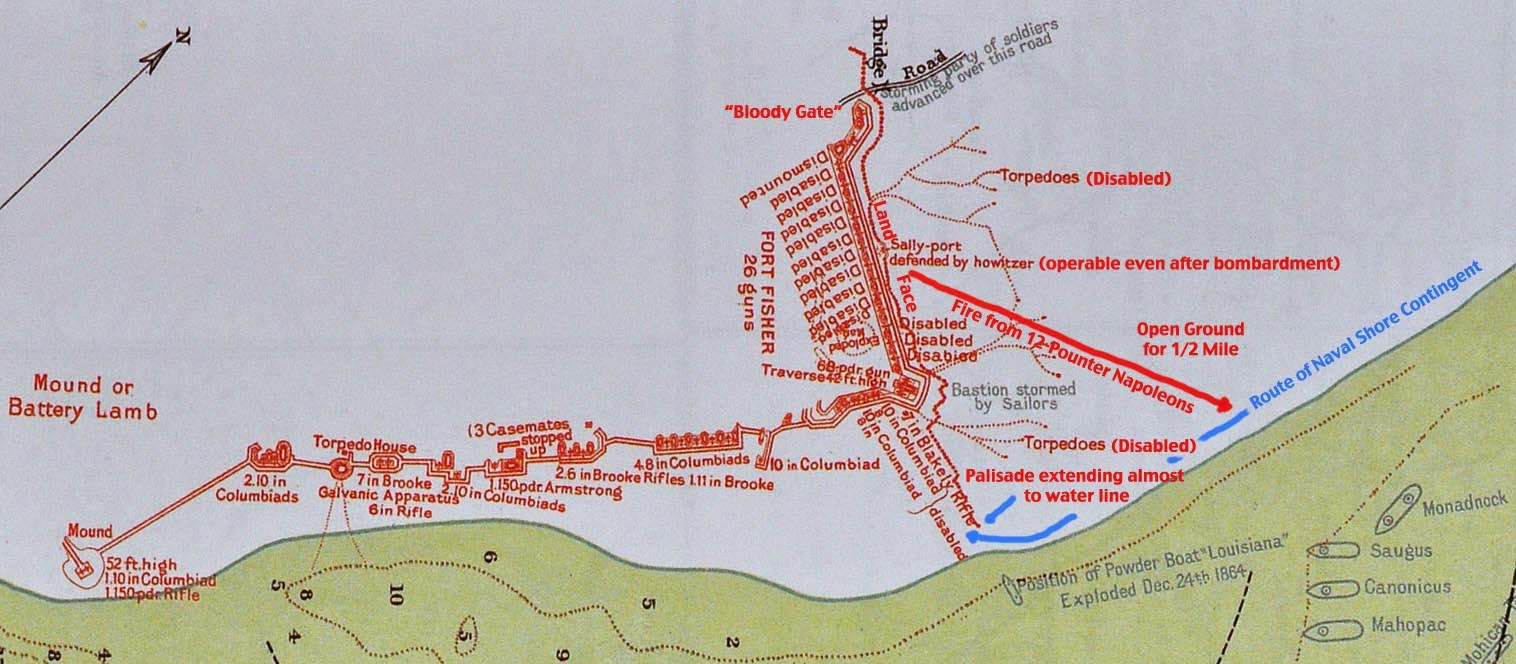

Nearly two months before, Parker had been in command of the double-turreted USS Onondaga and eight wooden gunboats dispersed along a 70-mile stretch between Richmond and Hampton Roads when the bulk of the Confederate Navy's James River Squadron, composed of three ironclads, five wooden gunboats, and three smaller torpedo boats, staged a desperate attack on the evening of January 23 to breach Union obstructions placed across the river. The week before, Commodore John K. Mitchell at his office within the Mechanic's Institute in Richmond faced a now-or-never decision. The grim news that Fort Fisher had fallen on January 15 hung in the frozen air. Wilmington, North Carolina; the last functioning port of the Confederacy and lifeline to Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia, was effectively neutralized. The city, buttressed by other fortifications guarding its approaches on the Cape Fear River, continued its resistance against the Union Navy some weeks afterward, leveling the odds between Mitchell's James River Squadron guarding Richmond, and the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron's Fifth Division, commanded by Cmdr. Parker, tasked with defending the Armies of the James and the Potomac. The lion's share of Rear Admiral David D. Porter's North Atlantic Squadron was still tied up in the Wilmington Campaign over 300 miles to the south, portending the possibility of the Confederate Navy snatching a victory in Virginia from the jaws of defeat in North Carolina. Change, it seemed, was in the air. As it happened, the air was literally changing. A warm front sweeping across Virginia that week had also made conditions optimal for a naval attack against Union targets. During the middle of January, much of the snow across the river basin suddenly melted, unleashing a freshet, or sudden rise of fresh water, temporarily surging the river. Intelligence that the freshet had damaged Union obstructions at a bend in the river called Trent's Reach had also reached the Confederate commodore's desk.

If Mitchell had not yet made up his mind about attacking, Confederate Secretary of the Navy Stephen Mallory made up his mind for him. "I deem the opportunity a favorable one for striking a blow at the enemy, if we are able to do so. In a short time many of his vessels will have returned to the river from Wilmington and he will again perfect his obstructions," Mallory wrote to Mitchell.

Time was of the essence to take advantage of the spring thaw, the destructive water surge and the elevated river levels that came with it, as well as the apparent parity in opposing forces. These factors were temporary, but the James River Squadron's mission was simply to do what the Confederate Navy did best throughout the war: Wreak havoc upon the Union's commercial shipping. The plan entailed cutting off both the Army of the James and the Army of the Potomac from their base of supplies at City Point, Virginia, only about 15 miles south of Richmond, which was also the location of Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant's headquarters. "If we can block the river at or below City Point, Grant might be compelled to evacuate his position," Mallory wrote.

Before the sudden thaw and surging of the river, the Union obstructions confronting the squadron would have included a thick hawser supporting a net intended to catch Confederate torpedoes before they reached the main barrier, which was made up of 14 sunken vessels, including five schooners, connected by double spars or booms. This barrier was linked together by a one and one-quarter-inch chain spanning the river, supported by beams.

Thanks to the freshet, Confederate Lieutenant Charles W. Read, the daring young officer commanding the James River Squadron's torpedo boats, was able to inform Mitchell after his men scouted the area:SIR: The net which was stretched across the river above the obstructions in Trent's Reach is gone. The schooner that was sunk in the old channel, on the south side, has drifted down several hundred yards. The vessel that was nearest the north shore has been drifted ashore abreast of her old position. The two vessels on each side of the north channel have lightened up by the stern; their entire sterns are out of the water; their bows are under the water. There is no vessel to be seen in the north channel.

On the Union side of the now-fraying obstructions, the news was remarkably similar, if not quite as enthusiastic. "The condition of the river obstructions above us is bad; they are washed away by the freshet," Cmdr. Parker telegraphed City Point from his base at Aiken's Landing, replying to a query from Major General John Gibbons, commanding XXIV Corps of the Army of the James. "I do not consider our naval forces sufficient to prevent the possibility of the enemy's gunboats coming down at high water, should they make the attempt. I believe it impossible to replace the obstructions unless Howlett's battery [also known as Battery Dantzler] be first captured."![]() |

| One of the 10-inch Columbiads at what was known by the Confederates as Battery Dantzler overlooks the James River in this image taken after its abandonment in April 1865. Cmdr. William A. Parker's concern over the two Columbiads and two Brooke rifles overlooking the James about three-quarters of a mile above Trent's Reach at what he called "Howlett's Battery" prompted a cautious approach. (Civilwartalk.com) |

Two days before the attack, Cmdr. Parker received word from Brigadier General John A. Rawlins, Grant's chief of staff, that the Confederate order to attack had been given, and that he should "exercise more than usual vigilance to defeat any plan the rebels may have in contemplation upon the river." This would be easier said than done. No less than 10 of Parker's vessels were laid up at Norfolk Navy Yard with no word as to when repairs would be complete, and he had just given up two of his needed tugs to the Potomac Flotilla in Maryland.

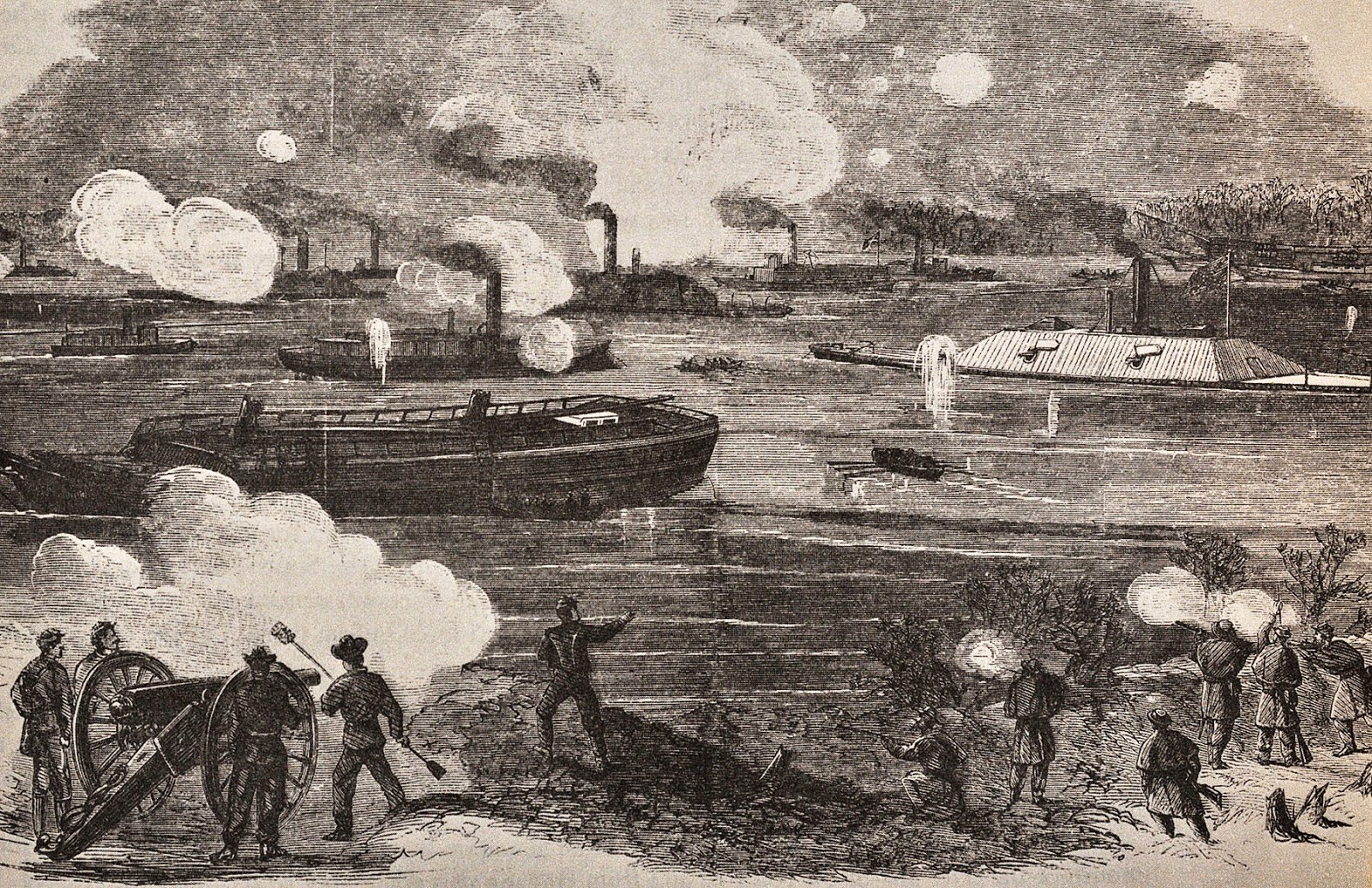

On January 23, the day of the attack, Parker sent a request to Maj. Gen. Gibbons that more vessels be sunk and torpedoes put in place that evening to make up for what had been lost, but by that time, it was too late. The confederate squadron got underway from its base at Drewry's Bluff at 6 pm, and about 5 hours later, Lt. Read began sounding out the north channel in a small boat as a team of Confederate Sailors hacked away at the remaining chains of the obstruction. Two hours after that, Commodore Mitchell ordered CSS Fredericksburg, the ironclad with the shallowest draft, through the obstruction. |

The Confederate Ironclads Fredericksburg, Richmond, and Virginia II of the James River Squadron lead eight other vessels including the gunboat CSS Hampton past the guns of Fort Brady at about 8 pm on the evening of January 23, 1865. (Harper's) |

Although sustaining damage from sunken hulks on either side, Fredericksburg, followed closely by the gunboat Hampton, made it through the obstruction, and behind enemy lines. The jubilation on the part of the insurgents would be short-lived, but not because of Cmdr. Parker or his Fifth Division, seemingly the only force left to opposing them. Nature herself had by this time turned against the squadron's other two ironclads, the flagship Virginia II and CSS Richmond. Both had run aground, and the remaining Confederate gunboats and torpedo boats were either grounded, abandoned, or even destroyed by Union shore batteries just downstream of the obstruction in the attempt to free them. Make-or-break time had once again come to Commodore Mitchell. He decided to recall the only vessels that had any hope of carrying out the mission. Both ships retreated past their marooned shipmates under what Lt. Read called "a perfect rain of missiles," to relative safety under the guns of Battery Dantzler. Lieutenant E.T. Eggleston of the C.S. Marine Corps, who was aboard Fredericksburg during the operation, wrote of his frustration a few days later:

This vessel passed through the Yankee obstruction at 1:30 a.m., and we all flattered ourselves that every difficulty had been overcome. The enemy's fire from their mortars had been quite troublesome for some time, but their heavy guns had not struck us once. After waiting for the other vessels for about an hour and seeing nothing of them, our captain sent me in a small boat to report to the commodore [Mitchell] that we were safely through and ask if we should wait any longer. I went up to the obstructions, and seeing nothing of them, continued for some distance before I came to them. After reporting, the commodore ordered me to return without delay and say to our captain that both the other vessels were aground and would not be able to get off before 11 a.m. the next day. This compelled our abandonment of all ideas of success, for the first requisite was a complete surprise, and before the next night they would have time to concentrate a large fleet above City Point.

By daylight, multiple Union shore batteries were finding their mark on the forlorn ironclads to surprisingly little effect, yet the question on Lt. Gen, U.S. Grant's lips, and on his telegraphers' fingertips, was, "What fleet has [Cmdr. Parker] collected or ordered to the front?"![]() |

CSS Fredericksburg, distinctive among Confederate ironclads because of her two pilot houses, had a shallower draft than her sister ship Richmond and flag ship Virginia II, which enabled her to pass Union obstructions at Trent's Reach when the others could not. When she was ordered back through the obstructions early on the morning of January 25, her weaknesses, lighter armor overall and a casemate covered only with iron grating, threatened to be her undoing. |

As the ironclad Fredericksburg and gunboat Hampton awaited further instructions amid their momentary mile-long foray past the Union obstruction, Cmdr. Parker ordered Onondaga nearly two miles back from her normal station at Aiken's Landing to a pontoon bridge spanning the James at about 2:45 am, where he promptly damaged one of his propellers attempting to bring the massive ironclad around.

![]() |

| These two models in the Hampton Roads Naval Museum gallery show that, even under optimal conditions, the fight between CSS Richmond (left) 180 feet long (minus the spar torpedo) and around 800 tons, and USS Onondega (right) 226 feet long and 1,250 tons, would have been uneven. The actual conditions on the morning of January 24 made matters much worse for the Confederate ironclad. |

Parker waited until around 8:30 to go back up the James. Meanwhile, Lt. Gen. Grant continued sending furious cables to Parker, but after hearing an explosion coming from the direction of Trent's Reach (which was actually the result of a direct hit upon the ammunition stores of gunboat CSS Drewry, abandoned and aground after the effort to free CSS Richmond), he moved up to Assistant Navy Secretary Gustavus Fox. Shortly after that, Grant issued "Special Orders to GUNBOAT COMMANDERS," which were ostensibly issued "By authority of the Secretary of the Navy," to "proceed to the front above the pontoon bridge, near Varina Landing." "This order is imperative," continued Grant, "the orders of any naval commanders notwithstanding." "I have been compelled to take the matter in my own hands to get vessels to the front, ordering by direction of the Secretary of the Navy," Grant informed Fox.

There seemed to be no objection on Fox's or Secretary Gideon Welles' part to Grant assuming direct command of US Navy vessels on the James River. In fact, Fox and Welles moved with dispatch, issuing orders to remove Parker from command and replace him with his deputy until Commodore William Radford and his New Ironsides could arrive from Hampton Roads.

![]() |

| This illustration from Harper's published February 11, 1865, depicts the scene at Trent's Reach around daybreak on January 24, 1865, after the ironclad Fredericksburg and the gunboat Hampton had made it through the gap in the Union obstructions created by the crew of the torpedo launch Scorpion (not pictured) at about 1:30 am. Yet after making it a mile past the obstructions, Fredericksburg was ordered to return after the ironclads Richmond and Virginia II became grounded waiting for the obstruction to be breached. Commodore Mitchell's decision doomed the only chance of the mission's success. Shortly after 7 am, the gunboat Drewry took a direct hit in its magazine and exploded, and Scorpion also had to be abandoned under fire. (A.R. Waud) |

When Onondaga did make her reappearance at around 10:45 am, along with the former ferry boat USS Hunchback and the side wheel steamer USS Massasoit, Parker was still in charge. Richmond was grounded at an angle in which her guns could not even be brought to bear, and she and the other ironclads were sitting ducks. Virginia II was struck over 70 times that morning from Union shore batteries, yet direct hits from Onondaga's 15-inch Dahlgren guns almost became the Union coup de grace. One shot tore a five foot square hole in her armor, killing one Sailor and wounding two others before the rising tide finally allowed the ironclads to make their escape.

"The monitor opened on us," wrote Lieutenant John W. Dunnington after surviving the pummeling aboard Virginia II, "and I am of the opinion that the two most damaging shots, one aft on port side of shield, and one between after port and port quarter port, were fired from the monitor." Richmond also sustained a hit from the much larger Union ironclad knocking away the port side gun port shutter. In contrast, one of Onondaga's whaleboats and two dinghies were "stove in" during the fight.

As the sun came up the following morning, Parker appeared on the double-ender gunboat USS Eutaw and, upon finding her commander, Lieutenant Commander Homer C. Blake, informed him that he had been removed from the command of the division "'by the honorable Secretary of the Navy.'" "'You being the senior officer present,'" Blake recalled Parker saying, "'I turn the command over to you.'"

Lt. Cmdr. Blake reported the exchange to Rear Adm. Porter, who had meanwhile joined the chorus of castigation concerning Parker, going so far as to say later, "Parker proved afterwards to be of unsound mind, though it was not suspected at the time, and previous to this fiasco stood high in the naval service both as a brave man and an excellent officer."

Two days after the battle, Parker outlined the preparations he had made, as well as the problems he had encountered before the attack, appealing to Secretary Welles, "I pray that you will order an investigation of the facts."

On March 18, Parker's prayers were answered in the form of a general court martial held aboard Baltimore. He was tried on two lengthy charges that essentially amounted to willful cowardice before the enemy. Although he had sent the order stripping Parker of command in the heat of the battle that day in January, Welles' attitude towards the incident had softened markedly by the time the voluminous specifications against the erstwhile commander appeared in black and white.

Welles surmised that many of the charges against Parker, such as that he "did order the U.S.S. Onondaga... to be moved down the river and away from the vessels of the enemy for the discreditable purpose of avoiding an encounter with [enemy] vessels," was practically unprovable, in that "[t]he ways in which an officer might fail to do his utmost to encounter and capture or destroy an enemy's vessel are innumerable." Furthermore, the secretary declared the allegation that Parker gave the order to move downstream for a "discreditable purpose" was not proved either, and that finding had thereby "virtually acquitted the accused of the charge of avoiding an encounter with the enemy."

Welles concluded:

It is to be inferred from the opinion of the individual members of the court, as stated in their individual recommendations for clemency, that the sole offense of Commander Parker... was "error of judgment." The Department is at a loss to understand whether the court considered "error of judgment" a crime in itself, or, under some circumstances, a valid defense against a proved crime. Neither can be sanctioned by the Department. The findings of the court ...and its specifications are not approved, and as the sentence... can now be modified, it is necessarily set aside, and Commander Parker is hereby relieved from arrest.

And with that, the sentence that Parker be dismissed from the Navy was vacated, and he was moved to the retired list.